Process - Using Field Recordings

Computer goes “Bleep bloop bleep bleep bloopity bloop. Whoosh. Bleep bleep… BRRRRR….”

If your generative music relies solely on synths and other electronic sources, it can quickly start to sound unnatural. How can this kind of music appeal to humans, who by their nature are more used to organic sounds and textures they hear day to day?

Field recordings of nature, or sounds that humans might hear day to day add back in context that might help listeners feel more engaged with the generative and more random aspects of the music. The sound of a stream, birds, rain, wind, people talking in a street and cars passing, even the hum or mechanical clicks of machinery can help the listener create a mental picture to go with the more abstract or generative ideas.

Balancing the natural and the (unnatural) randomness

Field recordings of natural, human sounds provide that balance between something familiar, predictable and natural with random bleeps and bloops. In Process - Balancing the unexpected and the predictable we discussed providing musical balance to the randomness. In this chapter we’re talking about using field recordings to provide that balance.

Natural and urban sounds

Take a walk in a woodland area. It’s never entirely silent. There’s likely the sound of wildlife, wind in the trees, perhaps the sound of water. By describing it to you now, I’m sure you have a mental picture (even though it’s sound!) of what you might expect to hear. Similarly, you can use urban sounds (street sounds), sounds from the house, mechanical noises - basically anything that listeners might be familiar with.

Randomness does occur in “natural” sounds

Consider the sound of a wind chime. The wind triggers the chimes at random, which are tuned to a pleasant scale… Sounds a lot like the generative techniques we’ve been discussing, right?

The sound of birds singing in the forest, with the odd chirp of a squirrel or the steady rasp of a frog. Nobody is telling them when to make sounds. It’s all pretty much random. So why (again!) is it that our brains think of these sounds as soothing?

I think the trick here is that we have context for the randomness. When we hear those sounds we know how they occur and where. But this underlines (at least for me) how adding context or something relateable to our compositions can help the listener engage better.

Recording noises

You likely have a phone with you now, or perhaps nearby. In that case you have a microphone to hand. So next time you’re out for a walk, take out the phone and record some noises. All you need to do is to be ready to listen and decide how the sounds you’re hearing are interesting, or how they could be contextualised (or provide context). The fidelity of these recordings doesn’t have to be astounding, after all, they are likely to be low in the mix. But minimising wind noise or handling sounds if you can will help the later “clean up” and integration of these sounds into the music. Use of EQ to remove low end or high end noises might be necessary.

Online sources for field recordings

Many producers create field recording sound packs, and some of these are sold through places like Bandcamp. Searching for “Field Recordings” should allow you to find these. Please do check licensing terms and conditions before you reuse these in your own compositions though!

Using the samples

You can use these as is, alternatively you might want to put the sample into Ableton’s Simpler and have a MIDI note trigger the sample but with random modulation on the sample start point. This will vary the starting point of the sample with each MIDI note and allow you to effectively extend the length of the sample to an arbitrary extent.

Granular processing

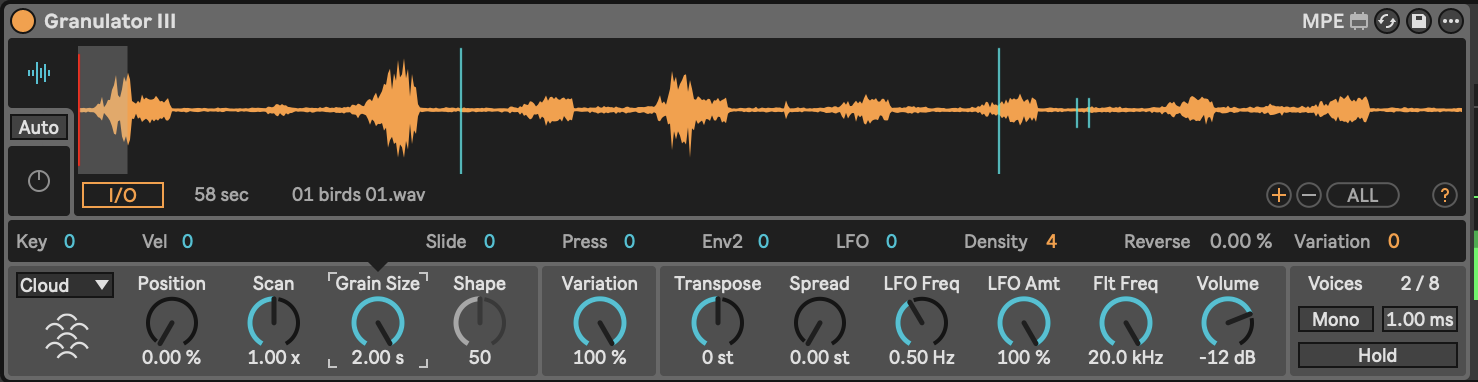

Another possibility is to use devices like Ableton’s Granulator III to process the audio. This takes an audio sample, and rather than playing slices of the audio it can play many grains of the sound, either short or long. The Granulator device needs MIDI input to trigger playback, but within the device you can specify position within the audio file, speed at which the grains scan through the audio, grain size etc. The beauty of this device is that it can take relatively modest length audio samples and using some randomness and LFO provide a constantly changing audio output.

Another benefit of granular processing is that you can produce audio that is related to the original audio, but processed to a point where it’s not immediately obvious what you’re hearing. The “DNA” of the original audio is still present, but it’s been smeared, chopped, and rearranged.