Process - Unsynced loops

“Around the world” - Daft Punk

Everyone loves a good loop. If you get a good idea of a pattern or something that lasts 8 bars then you can let that good thing just loop around and around and around (the world). A large part of The Lazy Producer’s arsenal depends on loops and repetition - after all we’re balancing predictable and unexpected, right? If a voice in your head is saying, “Wait, infinitely repeating 8-bar loops is the ultimate in Lazy Producing,” I’d have to agree. So how do we break away from the tyranny of the 8 bar loop? Arrangements? Verse-Chorus-Middle 8 structures?

Before you abandon the ideas of generative music (which doesn’t really lend itself well to arrangements, verses or choruses), there’s a trick up our sleeve which is to take our loops and make one of them shorter or longer than the other.

Making loops different lengths combines the predictable: each loop contains the same music idea each time - with the unexpected: the combination of those musical ideas each time the loop cycles creates something new and unheard.

Set phases to stunning

Minimalist composers like Steve Reich often worked with musical phrases that were repeated by each performer. By having phrases that were slightly different lengths, they would gradually go out of sync, but then wind up aligned at a different point in the phrase. This method coined the term “phasing” composition.

Sometimes the number of repetitions of each phrase was at the discretion of the performer, sometimes governed by the number of times the performer could play it in one breath, sometimes the composer worked with actual tape loops of different lengths. The concept is that while each part is repeated, the repeated parts move out of phase with each other and so create new sounds, rhythms and harmonies. No two performances would be the same, since the number of repetitions isn’t fixed.

Easy implementation in the DAW

Creating loops within the DAW is easy. Almost too easy. But often our “default” is to make those loops the same length. So the same ideas cycle round. But if we make the loops unequal lengths then it’ll take longer for those ideas to sync up. And if the loop lengths are not even - break out of the 2, 4, 8, 16 bar patterns - then it’ll take longer for them to repeat.

We actually used loops of different lengths in Recipe - Changing chords.

Don’t stop at notes

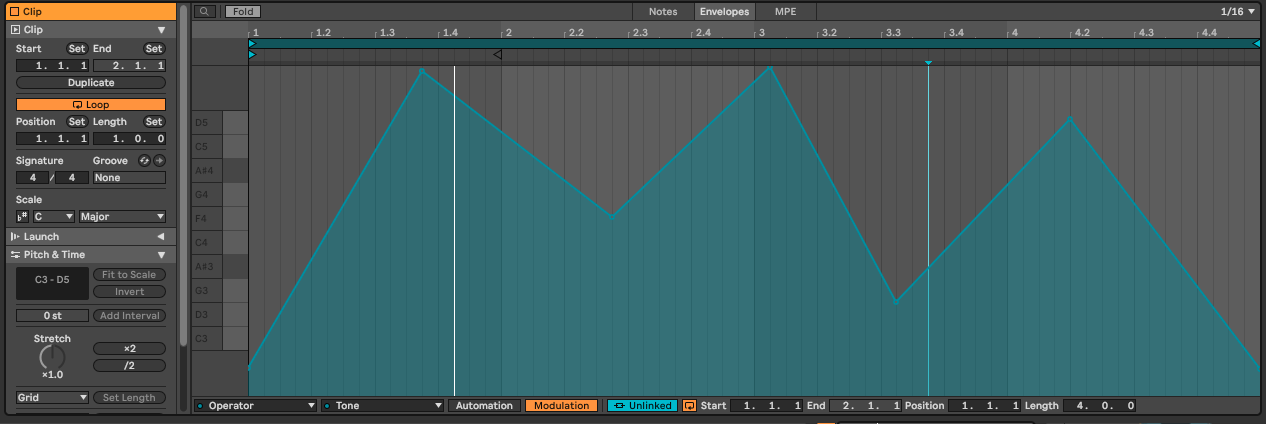

Another form of unsynced loop is where the modulation of a sound doesn’t vary over the length of the MIDI note loop, but has a different loop length. You can achieve this in Live by clicking on the Envelopes tab. In the image below we are modulating the Tone setting in the Operator instrument. The modulation loop has been set to “Unlinked” which allows us to draw modulation with a different loop length than the MIDI note clip length. Here the MIDI note clip is one bar but the modulation extends over 4 bars. By unlinking you can create additional variation in the sound of your loops and instruments quite easily.

I’m in my prime

If you recall basic maths from school, you’ll remember that you can break down most numbers into prime factors: 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19 etc. What this means for us as Lazy Producers is that if your loop is a prime number of beats / bars long then it’ll take MUCH longer for those loops to sync back up. If you have a 4 bar loop and an 8 bar loop then it only takes two repetitions of the 4 bar loop before you hear the same music idea again. If you have a 3 bar loop and a 5 bar loop then it’ll take 15 repetitions before you hear the same idea again. This means then that even for two musical ideas we get a lot of variety when you combine the loops even though both loops are repeating fairly often and fairly quickly. When you combine this idea across more than two loops you can get huge amounts of varying material with very little chance of repetition.

Fibonacci and the Golden Ratio

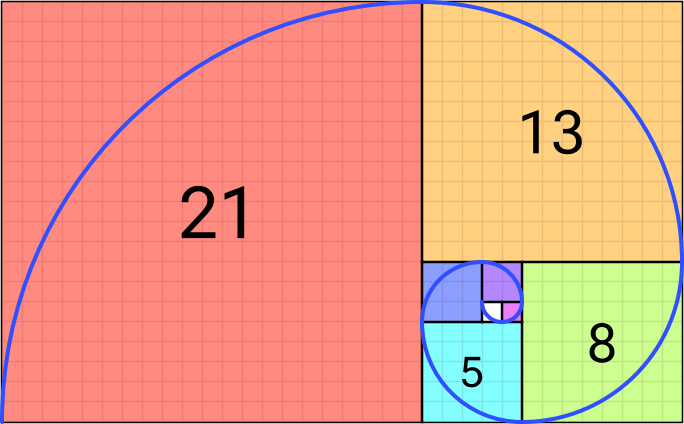

Primes are nice for preventing repetition in the grand scheme of things, but there are other options. Again, back to early maths and you might remember Fibonacci sequence where each number is the sum of the previous two numbers, starting with 0 and 1. So the first ten numbers are: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34. Notice that there are some prime numbers in there (2, 3, 5, 13) but also some even numbers (8, 34).

If you take the Fibonacci sequence and layout squares with their sides the length of the Fibonacci number, you get what is known as the “Golden Ratio” where the sizes of the squares grow in relation to the ratio of the previous two parts. There is a familiar pattern also if you connect arcs - quarter of a circle with radius equal to the size of the square. We often see this pattern in nature - in the pattern of seeds or petals on a plant.

I won’t pretend it has mystical properties (it’s just math, after all), but the mix of prime, even, and composite numbers in the Fibonacci sequence might be the perfect sweet spot of combining things that occasionally repeat and things that take a long time to repeat.

Suffice to say, it’s worth playing with some of these ideas to break out of the predictable loop and make something that perhaps could retain interest for a long period. In our next Recipe section we’re going to tap into this idea.

Let’s ROTATE

In discussion of Euclidean Sequencers in Tools - MIDI Generators we talked about how you can rotate a sequence so that it doesn’t start at 12 o’clock position (or on the first beat of the sequence). The same is true of loops. To break out of the predictable sequence you could choose to jump the loop start point to a different position. Sometimes small things like this will unveil new ideas, new rhythms which may be sufficient to keep interest.